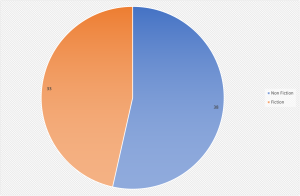

I read 70 books in 2011. Without counting, I am guessing that most of them are either a) novels or b) non-fiction read for either teaching or research, as these are the two categories into which most of my reading generally falls. This was a significant decline in quantity from last year, when I read 94, and that difference is mostly a result of the period in the spring when I was teaching four classes and doing not much else. I really only got to 70 because at the end of the year I found a bunch of books of less than 200 pages to get through quickly. All that said, here are my five favorite books from last year’s reading, along with a couple of honorable mentions.

1) Boxer, Beetle by Ned Beauman

This book involves boxing, beetles, homosexuality, Nazis, eugenics, rare diseases, and urban planning, all in a pretty seamless package. It could be classified as a black comedy; it is often indeed very funny, if more than a little unnerving. To be sure, Beauman’s reach sometimes exceeds his grasp, but it is his first novel and he is maybe 25 years old; I think that if he ever really gets hold of what he is going for, the result will be remarkable. I can already tell I am going to become an evangelist for this book, because it is one that makes you want to talk about it.

2) Hav, by Jan Morris

A piece of travel writing about a place that does not exist, but is entirely plausible. The narrator is “Jan Morris,” doing in Hav what she does in all her other books. The edition I read contains the original novel, from 1985, along with a sort of sequel describing Morris’s return to Hav in 2005. What is remarkable about the book is how cleanly Morris inserts Hav into world history; it was fought over in the crusades, invaded by the Ottomans, then held by the Russian empire, then divided up into an international League of Nations mandate after WWI. Every famous person of the late 19th and early 20th centuries seems to have passed through Hav at some point. The result is a place that is a kind of awkward mishmash of styles and influences, a place that makes it clear that being a “crossroads of history” does not make for happy, seamless cosmopolitanism. The sequel also demonstrates, with eerie clarity, how little the world is likely to tolerate this kind of promiscuous ambiguity.

3) 1984, by George Orwell

I had read this before, I think more than once, but not for a very long time; I re-read it because I assigned it to one of my classes. In retrospect, I think that in my own mind I had reduced the book to the caricature that is invoked constantly in our culture every time somebody refers to “Big Brother” or describes something as “Orwellian.” In that version, 1984 comes across as a kind of blunt-instrument warning about the importance of privacy in an age of pervasive technologies of monitoring. So I was surprised, perhaps stupidly, by just how good this novel is as a novel– how much fun it is to read, and how complex the ideas it contains actually are. It is indeed about a society in which citizens’ every action is watched and recorded, but it is also much more frightening than that.

4) Explorers of the New Century, by Magnus Mills

This is a story about two groups of explorers who take different routes in an effort to reach the Agreed Furthest Point, a place as far away from civilization as it is possible to get. There is very little else I can say about it without giving too much away; suffice to say it will surprise you. The writing is remarkably, maybe deceptively, spare and clear, so it moves quite quickly; but once I finished I was amazed at how subtly Mills creates one way of understanding the characters and their story, and then tears that apart completely.

5) The Whites of Their Eyes, by Jill Lepore

I expected this book to be about how stupid the tea party is– and, to be honest, I probably would have been fine with that. But Lepore is much smarter than that, and is doing something ultimately much more interesting. The Whites of Their Eyes is really about how the misunderstanding or misrepresentation of American history is, itself, a kind of American tradition, as we recast the events of our past to suit present political imperatives. It is as much about how to study, and how to use, history in general as it is about any one notion of the American past.

Also: The Lost Art of Reading, by David Ulin

The way this book is marketed makes it sound like it is making yet another argument about the fragmentation of our attention, about the problem of distraction, in a time when we have access to constant streams of information from multiple sources at the same time. And, indeed, Ulin mentions Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows, which makes this case in starkly neurological terms. However, Ulin is also saying something different about the consequences of reading many different things in short bursts, rather than one long thing, like a novel, that requires sustained attention. He suggests that reading novels, in which we engage with the thoughts and feelings of some other or others– and must engage with them if we are to understand them and their story– actually helps to teach us to empathize with others, to deal with a world in which similar kinds of identification and understanding are regularly required. I don’t know yet how much I buy this argument, or how far I would be willing to take it, but it is at least an interesting and, as far as I know, unique take on the importance of reading and literature.

Cesar Aira

A late-year discovery for me (as I sought short books to read) was this Argentinian writer, about whom I had heard much but read nothing. I have still only read one of his MANY short novels (or novellas)– he has published over 70, most around 100 pages long– and I did no necessarily love the one I read, taken as an isolated work. But I don’t think it makes sense to take any one of his books as an isolated work at all; rather, they should be seen as part of a larger project, one which I am very much intrigued about. Aira mixes standard literary fiction (if that phrase makes any sense) with images and tropes taken from genres like horror and science fiction in ways that are surprising and interesting, if not always necessarily successful. He is “experimental” in a way that is different from what that usually means in fiction, and I look forward to reading more of him in 2012.